Kepler's first law - Why don't planets move in circles?

1. What is Kepler's first law?

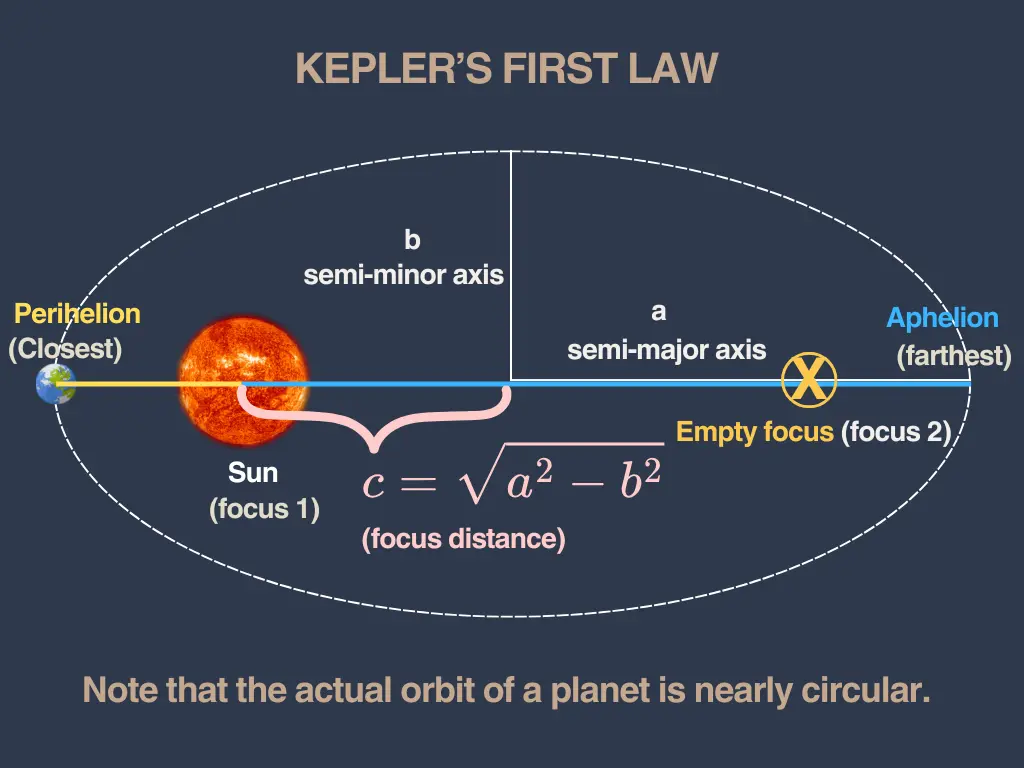

Kepler's first law states that every planet moves in an elliptical path around the Sun, with the Sun located at one of the two foci of the ellipse.

Before Johannes Kepler's groundbreaking discovery in 1609, astronomers believed that planets moved in perfect circular orbits. Kepler changed this view using observational data from the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe.

While working on the orbit of Mars, he realized that no models using circular orbits matched Brahe's measurements. Even his best best circular model still produced errors of 8 arcminutes. This is much larger than the measurement errors of Tycho Brahe, which is less than about 2 arcminutes. Kepler found out that an elongated circle (ellipse) matched the data better.

2. What is an ellipse?

To understand Kepler's first law mathematically, we need to understand what an ellipse is. In simple terms, an ellipse is a stretched circle. It is a closed curve where the sum of the distances from any point on the curve to two fixed points (called foci) remains constant.

Mathematically, an ellipse is characterized by the following:

Semi-major axis (a): half the length of the longest diameter of the ellipse.

Semi-minor axis (b): half the length of the shortest diameter of the ellipse, perpendicular to the major axis.

Foci (plural of focus): two special points located along the major axis. For planetary orbits, the Sun sits at one focus while the other focus remains empty.

Center: the geometric center of the ellipse.

The standard Cartesian equation of an ellipse centered at the origin is:

\[\frac{x^2}{a^2} + \frac{y^2}{b^2} = 1\]

where \(a\) is the semi-major axis and \(b\) is the semi-minor axis. When \(a = b\), the ellipse becomes a circle.

For orbital mechanics, the polar form proves more useful because it measures distance from one focus (where the Sun is located). The polar equation of an ellipse with a focus at the origin is:

\[r = \frac{a(1 - e^2)}{1 + e\cos\theta}\]

where \(r\) is the distance from the Sun to the planet, \(a\) is the semi-major axis, \(e\) is the eccentricity, and \(\theta\) is the angle measured from perihelion (the closest point to the Sun).

The eccentricity (\(e\)) is a dimensionless number between 0 and 1 that describes how much an ellipse deviates from a perfect circle. A circle has an eccentricity of exactly 0, while a highly elongated ellipse approaches an eccentricity of 1.

The eccentricity relates to the semi-major and semi-minor axes through the following equation:

\[e = \sqrt{1 - \frac{b^2}{a^2}}\]

Alternatively, if you know the distance from the center of the ellipse to either focus (\(c\)), you can calculate eccentricity as:

\[e = \frac{c}{a}\]

where \(c = \sqrt{a^2 - b^2}\).

3. Eccentricity values in our solar system

Most planetary orbits in our solar system have low eccentricities. Thus, planets have nearly circular orbits. Here are some examples based on data from NASA's Planetary Fact Sheet:

| Object | Eccentricity | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Venus | 0.007 | Nearly circular |

| Earth | 0.017 | Nearly circular |

| Mars | 0.094 | Slightly elliptical |

| Mercury | 0.206 | Moderately elliptical |

| Pluto | 0.249 | Moderately elliptical |

| Halley's comet | 0.967 | Extremely elliptical |

Venus has the most circular orbit of any planet in our solar system, while Mercury's orbit is the most elliptical among the eight planets. Comets, on the other hand, often have extremely high eccentricities, which is why they spend most of their time far from the Sun and only briefly swing close during their perihelion passage.

4. Perihelion and aphelion

Because planets follow elliptical orbits with the Sun at one focus (not the center), the distance between a planet and the Sun changes continuously throughout its orbit.

Perihelion: the point in a planet's orbit where it is closest to the Sun. The term comes from the Greek words "peri" (near) and "helios" (Sun).

Aphelion: the point in a planet's orbit where it is farthest from the Sun. "Apo" means "away from" in Greek.

You can calculate these distances using the semi-major axis and eccentricity:

\[r_{\text{perihelion}} = a(1 - e)\]

\[r_{\text{aphelion}} = a(1 + e)\]

The semi-major axis is simply the average of these two distances:

\[a = \frac{r_{\text{perihelion}} + r_{\text{aphelion}}}{2}\]

4.1 The Earth's orbit

Earth has a semi-major axis of approximately 1.000 AU (astronomical unit) and an eccentricity of 0.017. Using our formulas:

\[r_{\text{perihelion}} = 1.000 \times (1 - 0.017) = 0.983 \text{ AU}\]

\[r_{\text{aphelion}} = 1.000 \times (1 + 0.017) = 1.017 \text{ AU}\]

This means Earth is about 147 million km from the Sun at perihelion (early January) and about 152 million km at aphelion (early July 4). This 5 million km difference, while significant in absolute terms, represents only a 3.4% variation in distance.

4.2 Halley's Comet

Halley's Comet provides a nice illustration of Kepler's first law. Halley's orbit eccentricity is 0.967. It has a semi-major axis of about 17.9 AU. Thus, its orbital distances are:

\[r_{\text{perihelion}} = 17.9 \times (1 - 0.967) = 0.59 \text{ AU}\]

\[r_{\text{aphelion}} = 17.9 \times (1 + 0.967) = 35.2 \text{ AU}\]

At perihelion, Halley's Comet comes closer to the Sun than Venus. At aphelion, it travels beyond Neptune's orbit, nearly reaching the distance of Pluto. This extreme variation demonstrates how dramatic elliptical orbits can be for objects with high eccentricity.

5. Why is the Sun at a focus, not the center?

The Sun's position at one focus of the ellipse (rather than at the center) is a direct consequence of gravity. When Isaac Newton later developed his theory of universal gravitation, he showed mathematically that any object orbiting another under the influence of an inverse-square force (like gravity) must follow a conic section, which includes ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas.

For bound orbits (where the object doesn't have enough energy to escape), the path is always an ellipse. The central body, acting as the source of gravitational attraction, naturally occupies one focus. The second focus is just a geometric point without an object.

This positioning has important consequences. Because the Sun is not at the center, a planet experiences different gravitational forces at different points in its orbit. At perihelion, the planet is closer to the Sun and feels stronger gravitational attraction. At aphelion, the gravitational pull is weaker. This variation in gravitational force is directly connected to Kepler's second law, which describes how planets move faster when closer to the Sun.

6. Applications of the Kepler's firs law in modern astronomy

Kepler's first law extends far beyond the planets of our solar system. It applies to any object orbiting another under gravitational influence:

Exoplanets: when astronomers discover planets around other stars, they use Kepler's laws to determine orbital properties. The transit method, which detects planets by the dimming of starlight as a planet passes in front of its host star, combined with radial velocity measurements, allows scientists to calculate orbital eccentricities and semi-major axes. NASA's Kepler space telescope, named after Johannes Kepler, discovered thousands of exoplanets using these principles.

Moons: they are natural satellites orbiting planets follow elliptical orbits with the planet at one focus. Our Moon, for instance, has an eccentricity of about 0.055, meaning its distance from Earth varies between 356,500 km at perigee (closest approach) and 406,700 km at apogee (farthest distance).

Spacecraft trajectories: mission planners at NASA and other space agencies use Kepler's laws to design spacecraft trajectories. The Hohmann transfer orbit, commonly used to send probes to other planets, exploits elliptical orbits to minimize fuel consumption.

7. Practice activity

Test your understanding with this exercise. An asteroid orbits the Sun with a perihelion distance of 2.0 AU and an aphelion distance of 4.0 AU. Calculate the following:

- find the semi-major axis,

- calculate the eccentricity,

- find the semi-minor axis.

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a comment